By: Robin Everett, Wyoming State Archives

The following contains graphic accounts of assault and death. The language used in quotations includes racial slurs not considered acceptable today but are included for historical accuracy and context.

Lynching is a premeditated, extrajudicial means of execution by hanging, often by a mob, and often without a legal trial of the individual. Lynchings were not uncommon in Wyoming’s early history.[1] While most victims were white men, at least one white woman, and twenty-eight Chinese men [1A] were murdered in this manner. Accounts vary as to how many African Americans were lynched in Wyoming, though at least five are documented.[2]

In 1912 alone, there were fifty-two lynchings in the United States. Of that number, all but two were of African Americans. Alleged crimes against women or girls or accusations of the murder of a white person accounted for nearly all of those cases.[3] Wyomingite Frank Wigfall was one such case.

These pictures were taken during Frank Wigfall’s second stay at the Wyoming State Penitentiary between 1904 and 1912. He was released less than 6 months before his death. (WSA Wyoming Penitentiary mug shots, Inmate 806)

Frank Wigfall was either thirty-nine or forty-nine years old at the time of his death. He was born in South Carolina but his year of birth remains disputed. In his application for a pardon in 1911, he lists his birthday as April 15, 1862. However, the 1910 US Federal Census lists him as age 37, which would make his birth year 1872-73, as does his 1901 reception paperwork at the Penitentiary.[4] He very well may have been the child of slaves. Frank had never married and said he came to Wyoming around the age of twenty-four, after “wandering from here and there.” [5]

Frank Wigfall arrived at the State Penitentiary in June 1901, when this photo was taken for his inmate file. (WY Penitentiary mug shots, Inmate 570)

Wigfall first comes to our attention in 1901, when he is arrested in Cheyenne on the charge of assault with intent to kill. On April 9 he stabbed a young roust-about, Ollie Buckley in a local saloon. According to the newspaper account, Wigfall was warned several times about his loud conduct, and Buckley attempted to quiet him. Wigfall lunged at Buckley and stabbed him in the chest with a penknife. The knife struck the pericardial sac around the heart, leaving Buckley’s life in peril. Buckley and others in the saloon provided the county attorney with testimony of the event, leading to Wigfall’s arrest, conviction, and sentence of eighteen months to the State Penitentiary.[6] His reception paperwork at the penitentiary shows him as twenty-eight years of age.[7]

Cheyenne Daily Leader April 26, 1901, p4

Following his release, in 1902, Wigfall stayed in the Rawlins area, advertising in the newspaper as an “experienced colored man, does all sorts of house cleaning. Can be found at W. D. Davis’ saloon on Front Street”.[8] In 1903 he moved to Laramie and worked as a night foreman at the Union Pacific rolling mills. The mill made new steel rails out of high-quality recycled railroad track. While in Laramie, Wigfall shared a room with a co-worker at the mill named Dave Brown.[9] Dave was friendly with a white woman, Mrs. Kruppa, and her twelve-year-old daughter, Helen. While Frank had seen the women, he later asserted that he had not had any contact with them. [10]

On January 21, 1904, Wigfall was arrested in Laramie for the attempted rape of Helen Kruppa. Following his arrest and positive identification by both the girl and her mother, Wigfall, fearful of a lynching, agreed to plead guilty if authorities would take him away from the city. His fears were justified. Once the news became known around the community, “there was considerable talk among some of the more irresponsible citizens of a lynching”.[11] Justice was swift and after a hearing, Wigfall was sentenced to the full extent of the law, fourteen years. He was quickly put on the next train to Rawlins with Sheriff Cook. When he returned from the trip, Sheriff Cook reported that Wigfall had confessed to his crime during the ride. [12]

During his term in the Penitentiary Wigfall held several different positions. He tied brooms in the broom factory until his eyesight failed and made working in the dark difficult. He also worked in the kitchen, one of the few warm places in the facility during the winter, thanks to the ovens. Near the end of his incarceration, Wigfall became a porter and waiter in the Warden’s residence off of the Pen grounds. Only prisoners who earned the trust of the warden held this prestigious position and it meant Wigfall ate better than the inmates at the pen.

In April 1911, Wigfall applied for a pardon from Governor Joseph Carey. In the application, Warden Felix Alston stated that Wigfall “has been a perfect prisoner, will finish a fourteen-year sentence on the 28th of April 1912, and as far as behavior is concerned here it could not be better.” Alston also stated that Wigfall, “has been working for a few weeks doing porter work for me here, a good respectable and gentlemanly ‘darkey’ as one can meet.” Also, as part of his application, Wigfall offered that following his release he would be working for Frank Ryan in retail liquor.[13] Governor Carey did not grant the pardon, and Wigfall remained in prison for one more year.

Because of Good Time accrued, Wigfall was released from prison on April 15, 1912. Less than a month later, he ran advertisements in the local Rawlins paper offering his cleaning services. [14]

On September 30, 1912, Mrs. Esther Higgins was viciously attacked and Wigfall was accused of the crime. Mrs. Higgins, aged in her seventies, commonly known as “Granny Higgins” was well known to both the Rawlins community and the inmates of the Penitentiary. She would often visit, bring homemade baked goods for the inmates to enjoy.

According to newspaper accounts, late on the evening of the 30th, Wigfall broke into Higgins’ home by beating down the door with an ax. He sexually assaulted Mrs. Higgins, threatening her with death if she cried out for help. In the event of his discovery, he broke out a window for easy escape. Wigfall left in the early hours of the morning, leaving Mrs. Higgins to fend for herself. In her beleaguered condition, she was able to crawl to a neighbor’s house for help. Soon the authorities were on alert and the search began for Wigfall.

Word of the attack spread through the community and concerned citizens were told to be on the lookout for Wigfall as well. Wigfall was quickly captured by a posse at Fort Steele and brought the 17 miles back to Rawlins on the No. 3 train. A crowd gathered as Undersheriff Mills went to meet the train, but Wigfall was taken to the county jail without incident. In the meantime, Mayor Morgan had received a call from a concerned citizen warning him that some people were looking to take Wigfall from the jail and lynch him. Morgan acted quickly. He met with the Undersheriff, accessed the situation around the town, and asked for Wigfall to be transferred to the Penitentiary. Warden Alston was hesitant to take Wigfall though, explaining that he did not have the authority to do so. However, Alston told Morgan that if he could get approval from Cheyenne, he would allow the transfer.

During Morgan’s attempts to reach the Governor in Cheyenne, crowds were observed to be gathering around the courthouse.

“At 1 o’clock this morning a mob of citizens marched to the jail and demanded the negro. Sheriff Campbell refused to give up the prisoner and the mob dispersed to secure battering rams and arms. Two hundred strong; they returned in a short time, but in the interim Campbell had rushed the prisoner across two vacant blocks to the penitentiary, where he was locked in a cell on the fifth tier of the main cell-house. When the mob learned of the trick which had outwitted them and that the penitentiary guards had been ordered to fire if an attack was made on the prison, they dispersed quietly.”[15]

Undersheriff Mills and resident Jailer Hugo Rogner took measures to secure Wigfall’s safety. In case the jail was attacked, duplicate sets of keys were hidden in Rogner’s room.

In the meantime, Morgan was told the Governor was not in Cheyenne and that he would have to contact the Secretary of State. [15A] However, due to miscommunication, Morgan was instead connected to the Governor’s secretary, who explained that if Alston would accept his authority to authorize the transfer, he was giving it. Morgan relayed the information to Alston, who accepted the authority of the secretary. Wigfall was then secretly taken through the resident portion of the jail, out the kitchen, and across the courtyard to the penitentiary.

Wigfall was one of the earliest inmates at the newly opened Wyoming State Penitentiary in Rawlins. The first prisoners arrived in December 1901. Though “new”, the cornerstone had been laid 13 years earlier in 1888. Even in 1901, it was not a comfortable place. The building lacked running water, electricity, and adequate heating. The first addition, Cell Block A, was completed in 1904. (WSA Stimson Neg 992, 1905)

By the following morning, word had spread of Wigfall’s presence in the receiving cell. A fellow inmate, Rich, went to talk to Wigfall, “to find out what he had to say”. When Rich returned to report on the conversation, he was excited. He said that Wigfall did not seem worried about the heinousness of the crime. Boasting, Wigfall said “well I ain’t worrin’ any. Because I will be down at the warden’s house anyway after I get sentenced; if I get one year, five years, or fourteen years, why I can do that easy”. Wigfall apparently assumed he would earn Altson’s trust again and quickly return to working at Warden Alston’s residence downtown. [16]

After breakfast the morning of Wigfall’s return, inmates started their day by doing their assigned duties. One crew was busy scrubbing the floors, another working in the yard. The Cell House guard, John Neale was doing his morning inspections of cells on Tier 3. As a rule, the cell inspection guard was unarmed, which was the case with Neale. Suddenly, what he estimated at 35-40 men overpowered him, locked him in a cell, and warned him to keep quiet.

Guard David Brinton was on Death Watch. Because of the wet floor, he was not able to walk the full length of the cellblock. As he turned, he noticed Wigfall going up the stairs with a rope around his neck. Brinton jumped over a table and sounded an alarm by ringing a bell. Brinton did not see any other guards in the area. By the time he returned to where he observed Wigfall going up the stairs, he saw Wigfall hanging from a rope. He then heard Neale calling for assistance, and rushed to find him and release him from the cell. Both men estimated this all took about five minutes. Neither guard could identify any of the prisoners with Wigfall, or those who locked Neale in the cell. Four inmates who were part of the scrubbing crew were brought into the inquest, but they also could not identify the other prisoners. [17]

Following the Coroner’s Inquest, it was announced that “the jury has been successful in establishing one conclusive fact. It is certain that Wigfall is dead.”[18] According to Alston, a warning was passed out to all prisoners, and possibly guards, that ‘The first man that squeals is the next man hung,’ The Warden would not divulge his source of the warning.[19]

Even without the luxury of cable news networks, or the internet, the news spread across the nation quickly. Newspapers reported the story in a variety of different ways, from large sensationalized headlines to small noted articles. “Convicts Keep Secret Pact – Full details of Lynching May Never be Known”,[20] “Lynched in Penitentiary – Mob couldn’t Break in but Prisoners Ended Life of Frank Wigfall.”[21] The mystery continued even after the press became bored with the story and moved on. Officials despaired of ever finding out the truth. Decades passed and many forgot about Wigfall and his gruesome demise. That is until an anonymous diary entry was given to the Carbon County Museum.

The pact of silence was finally broken by the anonymous author of the manuscript that would be published in 1994 as The Sweet Smell of Sagebrush.

In 1994, the Friends of the Old Penitentiary in Rawlins published a manuscript that had sat in the museum collection for decades. Written by an anonymous author, The Sweet Smell of Sagebrush: a Prisoner’s Diary 1903-1912 follows a serial horse thief’s halting and often failing efforts to go straight and make an honest man of himself. His failings often land him back in the penitentiary, where he writes candidly about life behind bars in Rawlins. And this anonymous author becomes the one to break the pact of silence and tell the harrowing full story as he witnessed it.

Cells in the State Penitentiary were arranged in three tiers opening onto a common walkway or gallery. (WSA, SPEN-98, Not Dated)

“A small bunch of men came in the outside door as though they were about a half hour late for dinner and hungry as wolves. And they were late and hungry as wolves, but not for dinner. The little delegation was made up of such gentlemen as Burke, Paseo, Howard, Brink, and Elliott. They were mad as though to continue their way through the kitchen into the cell house, and Wigfall. Brink interposed between them and the door. The rope was dumped from the can and thrown out on to the floor where the kinks were run out. Brink said, ‘Now wait a minute fellows, two of you go into the cell house and capture Jack (the cell house guard). Take the keys away from him, lock him in a cell. Don’t hurt him.’ Two men turned and ran through the door into the cell house to overpower the guard and the whole outfit followed right on their heels. Brink and one other ran down the south side of the cell house looking for Jack. There were a few men in sight as it was early and they had not even started the usual morning’s work, such as sweeping the floor and so on. There was a man named Jenkins in the condemned cell at that time the guard who was acting as death watch was standing plain view in front of the death cell. He started to look out the window to sound the alarm but was confronted by one of the invaders armed with a knife. He was ordered to the back of the cell house, and he obeyed. The guard they were looking for was nowhere in sight. Brink ran clear around and through the alley to the north side of the place, as he emerged from the alley he ran out so he could look upon the galleries, at the same time saying, ‘I wonder where in the same hill Jack can be.’ The rest of the lynchers had gone down the north side and were congregated in front of the Wigfall’s cell. Jack was walking the galleries, the first one above the floor right above Wigfall’s cell. He held the keys in his hand the same as usual. Brink leaped upon the table and from there to the gallery. He grappled with the guard, who struggled to free himself. He was anything but a strong man physically and was helpless in the grasp of the husky blacksmith Brink. Burke leaped from the table and grasped the bunch of keys which he jerked from Jack’s hand. The keys were in turn snatched from the hand of Burke and the door of Wigfall’s cell unlocked in a twinkling. Wigfall could be seen cowering in the farthest corner. He was instantly grasped and yanked out through the door where the rope was thrown in a double half hitch about his neck. From the time when he was pulled from the cell, he never had an opportunity to stand still, the outfit went at double quick time towards the stairs to the galleries. Wigfall was clothed only in a night shirt. Rich didn’t want to be seen with the outfit and after they got to the stairs, he went back in the direction of the tailor shop. They went up the stairs to the top gallery and stopped at the place where previously a man committed suicide by jumping off the gallery. Wigfall was ordered to jump off the gallery but didn’t seem anxious to obey. He was menaced by a knife in the hand of Paseo. He asked that he be allowed time in which to pray. He was told that if he could make it short enough that he would have time to offer a prayer while making the decent [sic]. He was forded over the railing and he went down hand over hand like a sailor. He dropped and caught the railing on the gallery below. He was instantly dislodged from there by one of the party who had gone downstairs to forestall just such a move. He fell to the end of the rope. He was then drawn up by those at the top and dropped the entire distance again a few minutes later. In a few minutes, somebody ran out to where the men were working on the shop building and shouted, ‘Wigfall has been hung!’ The men outside all dropped their work and ran to the cell house. They secured a large packing case and placed it under a window. From a position on the box they could see into the cell house. They hung on each other’s clothes in the effort to climb up to where they could get a view of what was inside”. [22]

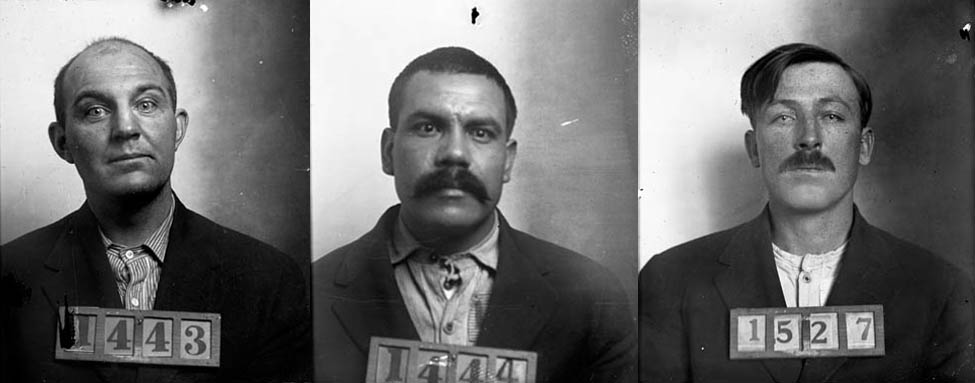

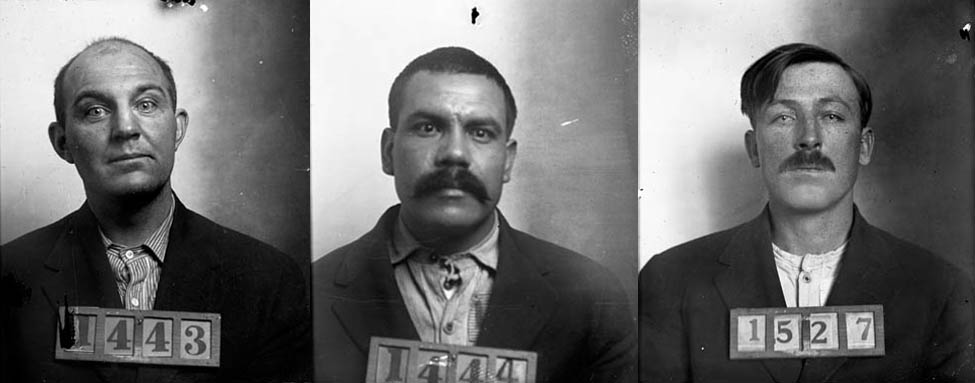

Herbert Brink, Lorenzo Paseo, and Robert Elliott were named by the anonymous author as members of the group of prisoners who lynched Wigfall in 1912. Brink (Inmate 1443), a former blacksmith from Big Horn County, was serving a life sentence for 1st degree murder. Paseo (Inmate 1444), a laborer from Mexico, was serving a life sentence, commuted from death, for 1st degree murder. Paseo was killed in October 1912 during an escape attempt. Elliott (Inmate 1527) was a repeat offender from Carbon County serving 2-3 years for forgery. (WSA, Wyoming Penitentiary mug shots)

While this account clears up who was involved, it still leaves the question of motive. Was Frank Wigfall lynched as a form of prison justice, because he bragged that serving any amount of time for the crime was going to be easy whether he did it in the kitchen or at the warden’s house. Was he lynched for the alleged crime against Mrs. Higgins? Or was there something else? What part did Wigfall’s race play in the fact – and the form – of his murder? Only those involved know the answer to those and many other questions surrounding the death of Frank Wigfall.

Resources

1. Davis, John W. Goodbye, Judge Lynch: the End of a Lawless Era in Wyoming’s Big Horn Basin. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, c2005.

1A. In 1885, 28 Chinese mine-workers were lynched during the Rock Springs Massacre. The racially charged riot was initiated by white miners who resented Chinese miners brought in by the Union Pacific Coal Company to break a miners strike. The result was robbing, looting, assault, and near-total destruction of Rock Spring’s Chinese community.

2. Davis, John W. Goodbye, Judge Lynch: the End of a Lawless Era in Wyoming’s Big Horn Basin. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, c2005.

3. The Andalusia Star, Andalusia, Alabama; Jan 2, 1913, Page 8 (newspapers.com)

4. Ancestry – 1910 US Federal Census accessed on June 5, 2020

5. Governor John Carey – Applications for Pardon – Wyoming State Archives

6. Cheyenne Daily Leaderno. 187 April 26, 1901, page 4

7. Board of Charities and Reform Records – Bertillon Book

8. Rawlins Republican October 25, 1902 pg. 5

9. Governor Joseph Carey – Applications for Pardon – Wyoming State Archives

10. Governor Joseph Carey – Applications for Pardon – Wyoming State Archives

11. Laramie Boomerang no. 268 January 21, 1904, page 1

12. Semi-Weekly Boomerang no. 79 January 25, 1904, page 4

13. Governor Joseph Carey – Applications for Pardon – Wyoming State Archives

14. Carbon County Journal no. 42 May 24, 1912, page 8

15. Wyoming Tribune no. 236 October 02, 1912, page 1

15A. According to Wyoming’s rules of succession, the Secretary of State serves as acting governor in the event that the Governor is either out of state or unable to fulfill his duties.

16. Hudson, William Stanley. The sweet smell of Sagebrush: a prisoner’s diary, 1903-1912 / written anonymously in Wyoming Frontier Prison, Rawlins, Wyoming. Rawlins, Wyo.: Friends of the Old Pen: Old Penitentiary Joint Powers Board, 1994

17. Carbon County Clerk of District Court – Coroner Inquest, Frank Wigfall October 2, 1912

18. Laramie Republican (Weekly ed.)no. 16 October 12, 1912, page 7

19. Tribune Stockman Farmer no. 80 October 04, 1912, page 1

20. Slaunton Daily Leader – (Slaunton Virginia) October 4, 1912 pg. 1 (Newspapers.com)

21. New Castle News – (New Castle, Pennsylvania) October 2, 1912 (Newspapers.com

22. Sweet Smell of Sagebrush

41.791070

-107.238663