Guest post by A. Rochaun Meadows-Fernandez

Our guest blogger is A. Rochaun Meadows-Fernandez. A writer and researcher who visited the State Archives, she discovered something she didn’t expect to see in our collections: herself. We were delighted to read her account of her visit, and to share it with you.

This essay was originally published in The New Territory magazine, Issue 9, 2020.

I was fresh out of college with idealized images of life after graduation when my new husband dropped two bombs on me. The first: He’d decided to go active-duty military. The second: We would be moving to Wyoming soon, and he would go ahead without me to find us a home.

Born and raised in the diverse and highly populated Dallas, Texas, I had no intentions of moving. I felt blindsided by my lack of choice and the mere three months I had to prepare. I was anxious about leaving my family and experiencing such a huge shift in demographics.

During the ride there, as the city streets I’d grown accustomed to faded and dirt roads became the norm, my apprehension multiplied. How could a city girl like me adjust to this new world? And how would I find community when my research indicated that less than 2% of the population in the entire state was Black like me? I secretly wished for a call from my husband saying he’d changed his mind or — better yet – that it was all just a practical joke.

The first couple of weeks were spent in denial. I’d arrived on a long weekend, so my husband and I were able to enjoy our honeymoon phase we didn’t have while living with family. But when I finally stepped out into the brutal Wyoming winter, I could no longer pretend that nothing had changed. The snow and the people were all foreign to me, and I longed to return home. I was both literally and metaphorically surrounded by whiteness.

The demographics weren’t much better on the base. There were many military spouses, but few of them cared for my conversations on the Black experience or my feelings of loneliness as a Black woman. I remember crying my eyes out after walking into Spencer’s at the local mall and seeing a wall adorned with a wide range of Confederate flag paraphernalia. I was resentful towards my husband for having brought me here and angry at myself for coming. By the third month, I’d given up on making friends or feeling like I would belong. But I refused to stay in the house. The quaint layout of downtown reminded me of the university town where I’d spent the last four years, and I was curious about what secrets hid behind the weathered buildings.

It took over a year before I ended up at the Wyoming State Museum and found its best-kept secrets.

The bulk of the museum was dedicated to retellings of settling the West and its rich history of natural resources. Yet the milestones of women’s suffrage and the inspiring stories of Native resistance piqued my interest, though I didn’t feel either was thoroughly covered in these displays. I wanted to know more about marginalized people who made it despite being othered. My curiosity led me across the hall to the Wyoming State Archives.

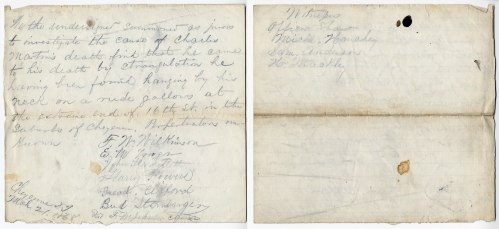

I began by flipping through images and newspaper clippings related to women’s and Native histories in Wyoming. After a short time, I gathered the courage to ask if there were records about Black people. The volunteer laughed at my question and replied, Of course! Within minutes I was nose deep in stories and photographs of Black Americans in 18th-century attire who inhabited the Midwest. My heart raced with joy upon realizing I was far from the first Black person to reside in the Plains. Not only did we exist – we often thrived.

For Black Americans, the West offered an opportunity to work in isolation from the rest of the nation. The region was so underpopulated that work ethic could potentially outweigh race, and Black settlers took advantage of the opportunity. There were photographs of Black landowners who even sustained full communities. It was impossible not to see my connection with these early Black settlers. My husband and I were also seeking a better life and had hoped to gain financial independence and to start a family in the sparsely populated state. With each image, I started to feel less like a random demographic dot and more like the continuation of a long thread of Blackness.

Despite being called “The Equality State,” things weren’t equal for Black Americans. However, I was also shocked to find that, in some ways, Wyoming’s treatment of Black Americans had been less harsh than other regions. For example. in November 1869, Black women in Wyoming Territory became the first black women in the nation to gain the right to vote1. I also learned of the Buffalo Soldiers2, the all-Black 9th and 10th cavalries whose earliest members were mostly ex-slaves, and how they accomplished noteworthy missions despite fighting both a war and racial adversity. They are even memorialized as statues right outside the military base.

But the mid- to late 1800s were long before my time, and I craved more recent examples of our footprint on the territory. It didn’t take long to find it. I quickly learned the Black citizens of Wyoming didn’t allow their low numbers to shock them into silence.

Harriett Elizabeth “Liz” Byrd3, whose grandfather. Charles Rhone, arrived in Wyoming Territory as a child in 1876, was the first example. A fourth generation Wyomingite, Byrd went on to be the first fully certified, full-time black teacher in Wyoming and the first Black woman elected into the Wyoming legislature, having served as a state representative and later serving in the Senate. Her husband, James Byrd, was retired military and served for 16 years as the state’s first Black police chief. The Byrd family legacy is a long list of noteworthy accomplishments and community first. But it’s vital to mention that the road was far from easy. It included intense encounters with those who adamantly resisted racial equality and change in the Midwest. Liz and James Byrd had three children, one of whom is currently involved4 in Wyoming politics.

On top of that, long before Colin Kaepernick, The Black 14 and several other Black students at the University of Wyoming were expelled after wearing armbands in protest of several political issues5. I felt pride knowing that regardless of where we were, we found ways to take a stand against injustice. Wyoming might have been mostly white, but the history went far beyond whiteness.

I’d been lost in the archives for hours. Just hearing the stories gave me a sense of belonging, and my willingness to find my place was renewed. I knew the thread of Blackness hadn’t stopped in the ‘60s, so I started looking for the remnants of Black social change in Wyoming today. Coincidentally, I heard about the Black Heritage Month celebration and, a few months later, I finally found the community I longed for. When I entered the church-held event, I saw pew after pew of Black Wyomingites. I started to cry. Like most places, faith was what held the Black community of Wyoming together.

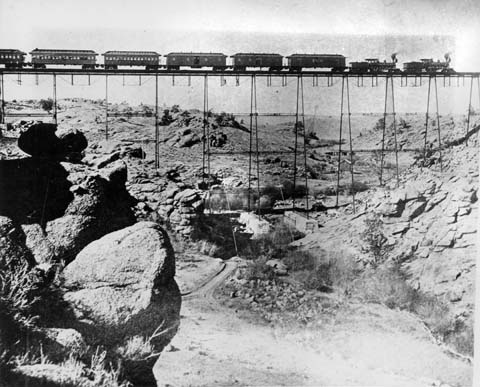

I began meeting more Black elders and asking their stories about migrating here. Many had been here for three or four generations. Their parents and grandparents came seeking opportunities with the railroads, military and agriculture. For them, Wyoming was the only home they’d ever known. I began asking myself why I thought I didn’t belong here — and why I felt my presence here needed to be explained. My predecessors and these living elders had already explained their presence, so I didn’t need to explain mine.

With time, I started seeing more young Black military migrants navigating the same things I’d experienced. I’d tell them that it gets better, let them know we are not the first nor the last, and I made it a priority to suggest they visit the State Archives, too.

Almost five years later, I’ve met so many people and heard so many stories. I still see the occasional Confederate flag, but now I know they have no ties to the territory of Wyoming. My people belong here just as much as anyone else. And as my husband and I raise our two children here, I look forward to passing on that message.

Wyoming isn’t home for good. But it’s a good home for now.

FOOTNOTES

- Tom Rea, “Right Choice, Wrong Reasons: Wyoming Women Win the Right to Vote,” https://wwwwyohistoryorg/encyclopedia/right-choice-wrong-reasons-wyoming-women-win-right-vote

- Tom Rea, “Buffalo Soldiers in Wyoming and the West,” https://wwwwyohistory.org/encyclopedia/buffalo-soldiers-wyoming-and-west

- Lori Von Pelt, “Liz Byrd, First Black Woman in Wyoming’s Legislature,” https://www.wyohistoryorg/encyclopedia/liz-byrd-first-black-woman-wyoming-legislature

- Joel Funk, “Cheyenne Democrat James Byrd to run for Wyoming Secretary of State,” Wyoming Tribune Eagle, https://www.wyomingnews.com/news/local_news/cheyenne-democrat-james-byrd-to-run-for-wyoming-secretary-of-state/article_0b336600-0d69-11e8-ad2c-4fe44ed691bf.html

- Phil White, “The Black 14: Race, Politics, Religion, and Wyoming Football,” https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/black-14-race-politics-religion-and-wyoming-football