Last year, we answered some questions about A&E’s Hell on Wheels, a television series with the backdrop of the construction of the transcontinental railroad in the 1860s. Season 4, which was set almost entirely in Cheyenne (though it was filmed in New Mexico), wrapped up earlier this year and Season 5, set in California and Laramie, Wyoming, premiered last Saturday. Thanks to Netflix binge watching and series marathons preping for the new season, we’ve seen quite a bit of interest in our last fact or fiction and thought it might be time revisit HOW to update the Q&A in light of the events of Season 4. So before we say good-bye to the train and crew and get back to civilizing the plains…

Was John A. Campbell really governor? What was he like?

Yes, John A. Campbell was appointed Wyoming’s first governor, but the transcontinental railroad was already completed by the time he arrived in Cheyenne and he was really nothing like HOW’s Campbell.

Governor Campbell arrived in Cheyenne in May 1869, and the Territory was officially organized on May 19 when all of the appointed officers were sworn in. Read more about Campbell’s first days here.

Campbell was a gentleman and former military officer and worked hard to set a firm foundation for the new territory. He had his job cut out for him bringing order to the wilds of Wyoming. That being said, there is very little evidence that he interfered with local law enforcement nor that he participated in lynchings, fought with the railroad, was a land speculator, or was ever in jail in Cheyenne. In fact, beyond setting up a sturdy foundation for Wyoming’s government, he is most remembered for securing women’s suffrage in the state by vetoing a bill that would have reversed the law in 1871.

Was Sherman Hill as big an impediment to the railroad as they portray?

Yes, Sherman Hill was a very big challenge for the Union Pacific Railroad in Southeast Wyoming. The route had been chosen to avoid as many large mountains (and thus tunnels) as possible. The railroad preferred to build bridges rather than blast tunnels as bridges were much faster and less hazardous.

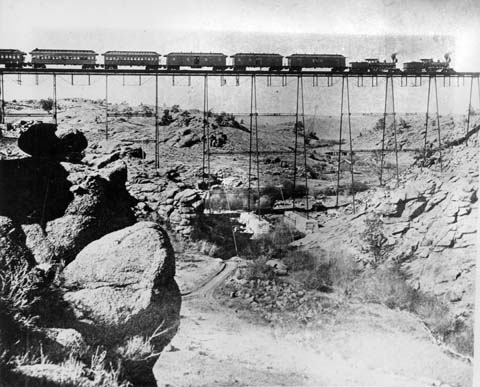

The 50 miles west of Cheyenne through the Laramie Range would be some of the most technically difficult miles of the route. Not only did this include the highest in elevation (8,236 feet above sea level), but they would need to cross a 127 foot deep, 1,400 feet wide canyon at Dale Creek after digging through solid granite for nearly two miles. While many of the major towns on the railroad had been set up 100 miles apart to provide water and coal for the engines, the towns of Laramie and Cheyenne are only 50 miles apart to account for the large amounts of coal and water needed to pull a train across the summit. It took a month to build the bridge using wood transported all the way from Chicago.

The wooden structure was replaced in 1876 by a stronger, more fire resistant iron bridge. But strong winds were still a problem.

(WSA Sub Neg 9779)

The challenges were only beginning when the tracks were completed. The winds, normally steady and strong in southeast Wyoming, would scream down the Dale Creek Canyon causing the tressel to sway, despite guy wires that were attached not long after completion. The sway understandably unnerved the crews and passengers and would often halt traffic while they waited for the winds to calm. Even during relatively calm days, trains slowed to just 4 miles per hour. The UPRR also set up a watchman’s hut at the bridge to look out for sparks coming from the engines that could set the wooden tressel on fire. The bridge was replaced in 1875 with a spidery iron system. The girders were replaced with more robust versions in 1885. Ultimately, the tracks were rerouted through a less dramatic portion of Dale Creek and the iron bridge was dismantled. The piers are still visible on private land.

Was the Cheyenne Leader edited by a woman?

In our last truth or fiction piece, we established that yes, the Cheyenne Leader was a real newspaper, but alas, it was not edited by a woman. The editor was a man by the name of Nathaniel A. Baker. The other two Cheyenne papers were similarly published by men: The Argus by Lucien Bedell and the Rocky Mountain Star by O.T.B. Williams.

The first female editor in Wyoming wouldn’t make her debut until 1890, when sisters Gertrude and Laura Huntington purchased the Platte Valley Lyre in Saratoga. [1]

The Rocky Mountain Star printing house published a newspaper of the same name in early Cheyenne. Unlike the story in HOW, none of the three papers were run by women.

(WSA Sub Neg 8780)

Were newspaper pressed burnt?

Yes, but not often and not the Cheyenne Leader. Fire was always a danger for printing offices with their stacks of paper and inks in wooden buildings heated by coal or wood stoves. One stray spark could set the whole place on fire. But that was true for most of the wooden buildings in the early towns.

The Frontier Index was a traveling press that followed the railroad and printed from the end of the tracks towns. When the railroad crews moved camp, the press was moved, too. Brothers Frederick and Legh Freeman ran the paper from 1866-1868 under the name the Kearney Hearld. After moving the paper from Kearney to North Platte, they changed the name to The Frontier Index.

The Frontier Index set up shop in several Wyoming towns including Fort Sanders (just south of Laramie), Laramie City, Green River City, South Pass City, Fort Bridger, Bryan and Bear River City.

(Frontier Index March 6, 1868)

The Freeman’s reporting style was rather biased and controversial, stirring up the already rough element in many towns. The end finally came in Bear River City (Uinta County, Wyoming) in November 1868. The town was so notorious it was said to be the worst of the hell on wheels towns. The press was burned during the Bear River City Riot which also claimed the life of at least 16 people and torched almost all of the buildings in town. The particularly opinionated issue that had come out the day before probably did not help the situation. Legh Freeman resurrected the paper as the Frontier Phoenix in Montana a few months later, saying it would “rise from the ashes.”

1. The “Lyre Girls:” First Women Newspaper Owners in Wyoming, by Lori Van Pelt, WyoHistory.org. (accessed July 2015)